Latest NEWS

- Aswat Masriya, the last word

- Roundup of Egypt's press headlines on March 15, 2017

- Roundup of Egypt's press headlines on March 14, 2017

- Former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak to be released: lawyer

- Roundup of Egypt's press headlines on March 13, 2017

- Egypt's capital set to grow by half a million in 2017

- Egypt's wheat reserves to double with start of harvest -supply min

- Roundup of Egypt's press headlines on March 12, 2017

Leaked files expose how Diab used offshore firms in oil deals with govt

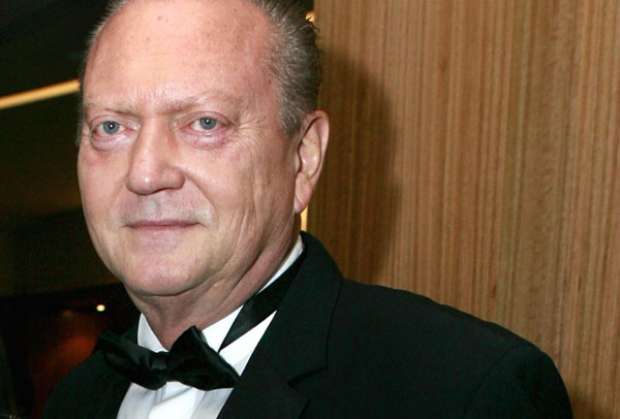

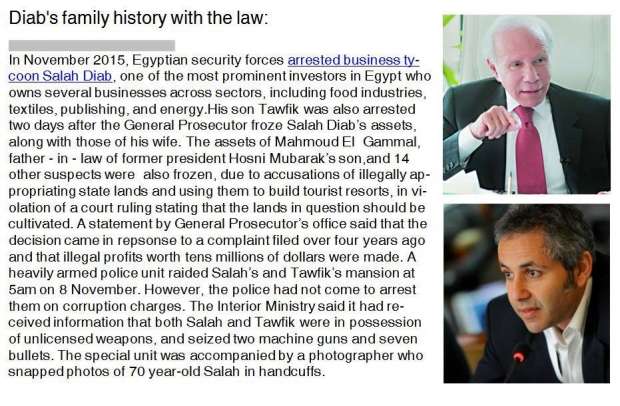

The family of Egyptian business tycoon Salah Diab used a corporate network made of Egyptian and offshore companies to sign agreements and strike deals with the Egyptian government, according to the second wave of Panama Papers released worldwide on Monday.

Asawatmasriya joins international media platforms publishing this second wave of The Panama Papers which is an unprecedented investigation that reveals the offshore links of some of the globe’s most prominent figures. The second wave focuses on uncovering Africa offshore empires.

The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), together with the German newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung and more than 100 other media partners, spent a year sifting through 11.5 million leaked files to expose the offshore holdings of world political leaders, links to global scandals, and details of the hidden financial dealings of fraudsters, drug traffickers, billionaires, celebrities, sports stars and more.

The trove of documents is likely the biggest leak of inside information in history. It includes nearly 40 years of data from a little-known but powerful law firm based in Panama. That firm, Mossack Fonseca, has offices in more than 35 locations around the globe, and is one of the world’s top creators of shell companies, corporate structures that can be used to hide ownership of assets.

Leaked data obtained by ICIJ reveal agreements involving the petroleum sector in Egypt. One of the agreements between Pico International Petroleum a subsidiary of Egypt’s Pico Group, and the Egyptian government concerned millions in development costs for the lucrative Al-Amal Petroleum Field located in the Gulf of Suez.

Tawifk Diab. Photo from his official Facebook account

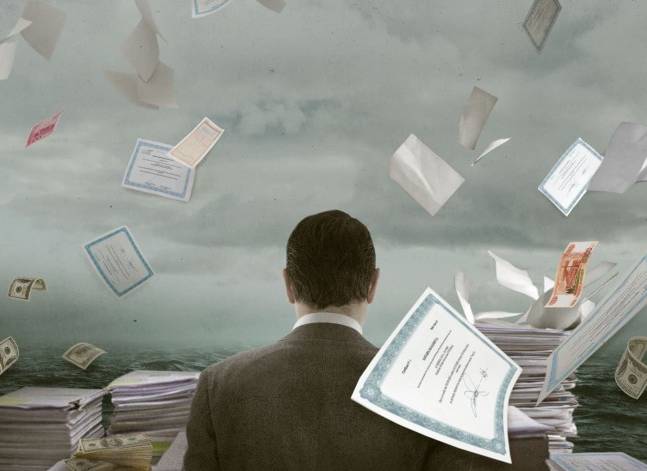

Several partners were part of this deal: the national oil company Egyptian General Petroleum Company (EGPC), Greystone and Pico International. Both Greystone and Pico Group are owned by the Diab family. Greystone is registered in the British Virgin Islands (BVI) while Pico is registered as an Egyptian company. The project involves the expansion and the development of an onshore processing plant.

Certificate of incorporation of Greystone Petroleum (Egypt) Limited.

The Egyptian government claimed to be unaware of the offshore activities involved in the agreement. When asked about these deals and the related documents, Tarek Al Hadidy, EGPC’s head said: “We have a concession agreement with them and they are committed to it. We don't know anything about the offshore activities of Pico International Petroleum & Greystone. My company [EGPC] is paying the taxes for Al-Amal field and if the other partner companies are involved in illegal activities, they should be investigated by the authorities, not by me.”

The issue of taxes is not as simple: the concession agreement of 2005 issued by law No. 159 allows for various tax exemptions at municipal and national levels and is exempt save for income taxes.

Pico International Petroleum is Egypt's largest locally owned oil and gas company. It works on developing smaller or more mature concessions that are a vital component of the country’s oil and gas sector. It is part of the Pico Group,which comprises seven independent sister companies, each enjoys managerial and financial autonomy.

Established in 1974, Pico Petroleum Services has grown to become a leading brand in the market segments it operates within, with offices in the Middle East, Europe, the United States, and Mexico. Pico is known primarily as a market leader in agriculture and the shareholders have been active in agriculture since the early 1930s.

Pico International Petroleum, directly or through one of its affiliates, owns interests in six offshore oil and gas assets: Zaafarana, Al-Amal, Gemsa, Geisum and Tawila West, West Tawila Marine, and South Ramadan Marine.

It had also interests in other countries including Romania and Mexico.

Due to local legislation in Egypt, interests in any oil and gas licenses are held by joint ventures (JVs) between the stateowned EGPC, holding 50% of the shares, and a private company holding the remaining 50%. In the JVs where Pico is involved, the company, and/or one of its subsidiaries, detains the majority of the private shares allocated to the contractor members.

It is unclear why an offshore ‘foreign partner’ was involved into an Egyptian deal when a local Diab company, Pico, was already there. What value did Greystone add, what income did it earn and what disbursements did it make? Were there any hidden owners present outside of the Diab family?

When Pico Group chair Sherif El Ezzawy was contacted for comment, he said: ““Regarding Pico Investment Seychelles and Greystone, I emphasise that both companies were lawfully incorporated following all laws and regulations. They were not, and are not, connected to any wrongdoing.”

He further explained: “Pico Investment Seychelles was founded in 2008 to invest in the Gulf area. We chose Seychelles because it offered attractive terms for foreign investors. After its establishment, we decided not to pursue the investment we were evaluating, and therefore had no use for the Seychelles company.”

Incorpration certificate of PICO investment limited.

El Ezzawy went on to say that the entity was inactive and throughout the period no transactions or transfers were done by Pico’s Seychelles company. Regarding Greystone, he claimed the entity was founded before it was acquired and, ‘inactivated as well in 2013.’

Having an offshore company is not a crime, meanwhile offshore companies are often accused of tax evasion and avoidance, the former illegal and the latter technically legal.

El Ezzawy said that offshore companies operating in Egypt are not exempt from taxes for their local activities, specifically in the oil sector. “Taxes are automatically and directly deducted and paid by the regulator on behalf of the partner. Such agreements are completely regulated through Production Sharing Contracts that are passed as a law through the Egyptian parliament.”

The documents uncovered by the Panama papers regarding this case do not show any wrongdoing by Diab’s family. However, they raise questions about whether the family benefits from any offshore tax strategies such as artificial management fees or for the use of bank accounts and whether their interests were fully disclosed.

Mossack Fonseca law firm sign is pictured in Panama City, April 4, 2016. REUTERS/Carlos Jasso

The story started in June 2008, when Tawfik Diab, the only son of Egypt’s tycoon Salah Diab, established a company called Pico Investment Limited in Seychelles. Mossack Fonseca’s Seychelles branch was the registering agent logging the company as no: 050605. Minutes of the company registration show that Tawfik Diab was elected as the chairperson of the meeting, and his relative Mohamed A. Kamel Diab acted as the secretary.

Mossack Fonseca emails and contracts show that Pico Investment was authorized to open a bank account with JP Morgan Suisse SA in the Swiss canton of Geneva. Tawfik was in charge of completing the transactions on behalf of Pico investment in Seychelles and managing all business with JP Morgan Suisse. Leaked data show that a portion of the shares of Pico Investment were divided between Salah Diab and Kamel Diab – each received 200 shares. Meanwhile, Technoil Limited Inc and Petroleum Ventures International Inc (PVI) each owned 400 shares. In 2013, the company was shut down.

Ramon Fonseca, founding partner of law firm Mossack Fonseca, speaks during an interview with Reuters at his office in Panama City April 5, 2016. REUTERS/Carlos Jasso

Diab’s family was also linked to another offshore company in the BVI, called Greystone Petroleum (Egypt) Limited. Corporate data for Greystone Petroleum (Egypt) Limited (no. 36154) that goes back to 2003 shows Salah Diab and Tawfik Diab as the directors. The company’s authorized capital of $10 million was divided into 100,000 shares and a per share value of $100 each. In February 2013, Mossack Fonseca decided to resign as a registered agent for Greystone Petroleum.

Greystone previously had a co-shareholder PVI, also a shareholder in Pico Seychelles. In 2013, PVI’s beneficial owner claimed in an email that his shares in Greystone had been sold to Tawfik in 2004. Greystone was described as a subsidiary of Petroleum Ventures. An internet search of the owner’s name results in senior positions across several Egyptian entities including petroleum and cement companies. A worried Pico employee sent an email, dated 2013, to Mossack Fonseca asking for advice on ignoring 'the BVI rule that majority shareholder consent is required’ and how they could ‘ascertain whether there is a legal/beneficial owner of assets attributable to PVI 599 shares in Greystone Egypt.’

Mossack Fonseca co-founder Jürgen Mossack.

So, what was the purpose of the hidden Swiss bank account administered from the Seychelles? Why hold millions of dollars worth of shares in an inactive offshore company? Experts we contacted said that companies are often created solely to host offshore banks accounts.

While the Panama Papers do not expose any wrongdoing, it would go a long way to rebuilding public confidence in state and private company partnerships of this kind, if the corporate structure, including ownership, was transparent and not obscured by banks in secrecy jurisdictions.

Business tycoon Salah Diab and his son Tawfik.

The article has benefitted from ANCIR's assistance